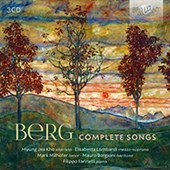

Alban BERG (1885-1935)

Jugendlieder (1901-08) [2:16:48]

Sieben Frühe Lieder (1905-08) [15:57]

Vier Lieder, op.2 (1909-10) [8:21]

Altenberg Lieder, op.4 (1911-12) [10:20]

Schliesse mir die Augen beide (1925) [1:07]

Lied der Lulu (1934) [2:56]

Klagegesang von der edlen Frauen des Asan-Aga Melodrama (1903) [8:26]

Mauro Borgioni (baritone), Elisabetta Lombardi (soprano), Mark Milhofer (tenor), Myung Jea Kho (soprano), Stefanie Köhler (speaker)

Filippo Farinelli (piano)

rec. 2018-2019, Perugia, Italy

BRILLIANT CLASSICS 95549 [3 CDs: 184.11]

The present 3-CD collection is billed as containing the complete songs of Alban Berg (1885-1935). A major feature of this release is the Jugendlieder, the early songs. From what I can make out (and I am no Bergian scholar) the order of the songs presented here are derived from the two volumes of manuscript songs rather than from the published edition. Volume 1 contains 34 songs and Volume 2 some 56, including the Vier Lieder, op.2 and the Altenberg Lieder, op.4 (1911-12). The composer expressed a wish that they should not be published. I understand that Universal Edition has issued three volumes of Jugendlieder edited by Christopher Hailey. I was unable to find complete details of this project, including batting order of the songs, on the Internet. The present CDs include Hailey’s editions appendices but not the few incomplete or spurious songs.

It would be redundant (and very long-winded) of me to provide a detailed account of each one of the Jugendlieder. I will say something about the collection itself and its overall stylistic parameters. The trajectory of Berg’s development as a composer can be judged from the progress of this collection. In the earliest of these ‘youthful’ songs, the listener will typically perceive nothing more revolutionary than music influenced by Schubert, Schumann, Wagner and latterly Gustav Mahler. As Berg’s technique matured, his stretching of tonality towards the atonalism of Schoenberg will become apparent. On this journey, there are also echoes of Johannes Brahms, Hugo Wolf, Richard Strauss, Maurice Ravel and Claude Debussy. It is no serious criticism to suggest that the Jugendlieder are sometimes a bit like the curate’s egg: good in parts. The integrity of these songs vary from the sublime to the tacky. The poets that Berg chose to set range from the well-known to the obscure but include Ibsen, Heine, Rilke, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson and Goethe. The subject matter includes nature, lost love, sadness and death. The earliest numbers date from the years before Berg’s studies with Arnold Schoenberg whilst a few later ones clearly display his absorption (and personal adaptation) of the master’s compositional technique. It is ideal to have the complete set of the Jugendlieder available in one CD set.

I first discovered Alban Berg’s Sieben Frühe Lieder (Seven Early Songs) on a Deutsche Grammophon album released in 1994. This featured the Swedish mezzo-soprano Anne Sofie von Otter and Bengt Forsberg at the piano. I fell in love with this music immediately. These were originally selected from Berg’s second volume of manuscript songs and were scored for medium voice and piano. They were published as a set in 1928. Berg also wrote an orchestral version of this collection with the vocal part transposed to high voice. This latter was not issued until 1955. The original songs were composed between 1905 and 1908 during the time Berg was studying with Schoenberg. Mosco Carner has suggested that the composer wished to show what his musical background was. By 1928 he was fully committed to the 12-tone methodology, so this was surely a backward glance. I regard these Seven Early Songs as being on a par with Wagner’s Wesendonck Lieder and Richard Strauss’s Four Last Songs. For me, the performance by Elisabetta Lombardi, does not quite match that of Anne Sofie von Otter, as her voice seems a little strained by comparison.

Vier Lieder was his second published work after the Piano Sonata, op.1. He had begun to study with Arnold Schoenberg in 1904 and had gradually absorbed much from his teacher. It is interesting to note that the first three songs have key signatures but are largely free from conventional harmonic structures. The final song abandons any sense of key and is Berg’s first work to completely suspend tonality. Even the briefest perusal of the score reveals the visual and aural complexity of these songs: it is an adventure in chromatic sound. The songs are all about sleep (and by implication, death). This is a clever conceit but makes for a subtle and beautiful journey into the arms of Morpheus.

The Altenberg Lieder, op.4 are based on ‘picture postcard’ texts by Peter Altenberg, a luminary of the Jung-Wien (Young Vienna) movement. These consist of short billet-doux supposedly sent by the poet to young ladies in the city’s coffee-houses to ‘chat them up.’ Berg made his settings during 1912 just prior to beginning work on his Three Orchestral Pieces. The song cycle’s premiere performance, on 31 March 1913, was subject to considerable disruption, if not rioting. The concert included Webern’s Six Pieces for orchestra, Arnold Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony No.1 op.9 and Alexander von Zemlinsky’s Four (of six) Orchestral Songs on poems by Maeterlinck. The event was broken up (literally) before Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder could be performed. All these works would now (2020) be regarded as masterpieces, if not universally loved! Berg’s Altenberg Lieder provide a link in his compositional development between the romantic world of Schumann, by way of the late romanticism of Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler, towards Expressionism which is the dominant feature of his two great operas, Wozzeck and Lulu. These lyrical songs are tightly constructed with constant internal self-referencing, full use of the chromatic scales, symmetrical formal structures as well as the full panoply of technical devices such as canon, passacaglia and variation. The accompaniment is always subtle. Musical influences must include Arnold Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder (1901-11) and Gustav Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde (1908-9). The Altenberg Lieder were originally written for voice and orchestra. It is heard here in the piano version which may or may not be by the composer.

Alban Berg set Theodor Storm’s poem Schliesse mir die Augen beide (Close both my eyes with your loving hands) on two occasions: Firstly in 1907 and then in 1925. This latter production is deemed to be the composer’s first completely 12-tone work (as opposed to atonal). It was dedicated to his publisher, Universal Edition, on achieving their silver jubilee. Interestingly, Berg uses a variant of this song’s tone-row in his ‘popular’ Lyric Suite for string quartet, written the following year. Schliesse mir die Augen beide is a perfect example of how much beauty (as opposed to an expected/perceived ugliness) can be derived from the dodecaphonic method of composition.

The latest work here is Lied der Lulu (Lulu’s Song) from the second act of the eponymous opera, still incomplete at the composer’s death. It was included in the orchestral Lulu Suite devised by Berg as a kind of advert for the opera. On this CD it is heard in the version for voice and piano. This wonderful coloratura song appears at the point before she kills Dr Schön. It is a powerful piece expressing the soprano’s self-justification which is splendidly sung here. It was dedicated to Anton Webern on his 50th birthday.

The final track in the three CD collection features a ‘melologue’ (spoken declamation) dating from 1903. Klagegesang von der edlen Frauen des Asan-Aga (loosely translated as ‘Death Lament by the Noble Women of Asan-Aga) is based on a Serbo-Croatian folk poem rendered into German by Goethe. I found an English translation of this poem in the poet’s ‘Complete Works.’ Berg has set these heart-breaking words for speaker and piano. It captures the sadness and depth of the original ballad. It is a little masterpiece.

I was disappointed that the CD booklet did not contain the texts and translations of these songs. I accept that this may have involved a considerable production cost. However, I am not sure whether there is an easy source for this material. The website Lied Text would be a useful place to begin, but I understand that due to copyright restrictions much of this is missing. The liner notes include an essay by the present pianist, Filippo Farinelli that gives a good introduction to Berg’s songs. There are the usual biographies of the performers.

I found this valuable release totally absorbing. It is convincingly performed from the first note to the last. Each performer brings sincerity and enthusiasm to this varied repertoire. The recording is ideal. It has given me the opportunity to explore a facet of Berg’s music that I did not know well. For all those interested in the major impact Alban Berg had on the music of the Second Viennese School and on 20th Century musical history, this is a perfect companion. For listeners who are ‘suspicious’ of atonality and twelve-tone music, this release will provide ample confirmation that this period of musical history could produce works that are both beautiful and moving. Finally, it is important to have a conspectus of Alban Berg’s vocal music from his early sub-Schumann days to his full-blown adaptation of the Schoenbergian ‘method’ to his own personal ends.

John France